Wiki article

Compare versions Edit![]()

by Hubertus Hofkirchner -- Vienna, 5 Jul 2015

Recently, we stumbled over a very strange survey result. In a screener questionnaire, which we ran before a prediction market study, almost 40% of “Weekly Grocery Shoppers” checked the box saying that they had a “University Degree or More”. Imagine that: according to this data, you are more likely to meet brainy graduates at your local supermarket than at uni where arguably, undergraduate students are in the vast majority.

Whoa ... this was well beyond the typical distortion levels of traditional surveys. Puzzled, we used our own server data to cross-check the respondent structure for the sample which we sourced from a leading global provider. The numbers from IT were shocking: they indicated that 43% of these respondents were duplicate participants, fraudsters.

Before the story continues, let’s look at this issue in context.

What motivates response fraud?

Response fraud is a form of cybercrime and a constant nuisance for the steadily growing online portion of market research. Fraudsters participate in online surveys to get the monetary incentive offered for their time without providing genuine answers. They enter as often as possible, with multiple email aliases creating an unlimited supply of fake IDs.

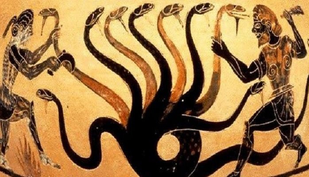

Online sample providers are fighting these many-headed cyber monsters with sophisticated security tools and spend significant effort on identifying and filtering sham respondents. The fraudsters in turn undermine providers’ filters with some simple tricks, helped by lots of web sites with tips how to “make easy money” with surveys.

The cost of response fraud

It is difficult to estimate the direct and indirect damage caused by response fraud. Direct damage is the cash cost of fake respondents and all research projects with invalid results, indirect damages arise when research clients are misguided in their business decisions through bogus results and insights which are not. It is easy to see that the resulting dollar number may be quite big.

A similar war zone, click fraud, may give us guidance. Click fraud is a rampant problem in online advertising. It denotes ads clicked by robots or humans with no intrinsic interest in the ad, but for some clever way to get a share of advertising spend. The Association of National Advertisers estimates that US businesses are losing US$ 6.3 billion a year to click fraud. Techcrunch recently reported that 80% of paid Facebook clicks come from robots.

For market research, the big associations like ESOMAR or ADM have not yet put a number on response fraud. A confidential source at a supplier estimates the typical level of unidentified fake respondents to be 5 to 10%, reaching up to 50% in rare cases.

The war against response fraud

Focusing on purely technical countermeasures -- it exceeds the scope of this article go into methodological ones like trick questions -- sample providers’ standard defence is to place a cookie on respondents’ devices to block them from participating more than once. It takes no genius to neutralise this measure. Shifty respondents can simply use multiple browsers, this also saves them the time for logout and login when changing their IDs. Fraudsters may also use private browsing or delete their cookies regularly; in fact, most modern browsers have a setting which automatically wipes all cookies after each session.

More advanced sample providers try to detect multiple registrations despite different browsers based on identical IP addresses. Here it starts to get more tricky for providers than for cheaters. Legitimate users may use the same IP address when browsing from work or school. All family members on a home network have the same IP address, not to mention tethering, Internet cafes or public hotspots. So, how many users with the same IP address should a provider allow? Further complicating the matter, private IP addresses are mostly dynamic; the address of one user today may be another’s tomorrow. A clever fraudster can also use a free IP anonymizer like Tor to fake his IP address with a simple click.

High-quality sample providers even capture digital fingerprints from unique timestamps for certain system component updates as their ultimate weapon, probably getting close to a point where privacy advocates start to show symptoms of rabies. Even this gives no guarantee: any fraudster can simply use his PC, tablet, and smartphone in parallel, and a work laptop for private use to boot, all with a different fingerprint.

Is this a losing battle?

Absolutely not. While traditional questionnaires are very vulnerable to this issue, you can largely sidestep it with a new research methodology. In my next blog, you will learn a simple way how to detect a tainted sample and how to get reliable results and insights despite fraudsters’ deceitful efforts.