Wiki article

Compare versions Edit![]()

by Hubertus Hofkirchner -- Vienna, 22 Aug 2015

Consistent with Switzerland's reputation as a model of direct democracy, the country employs many instruments to find out what its citizens think and want. Some tools they use, however, are getting outdated. For more reliable and accurate results, Switzerland should embrace innovation and the internet.

The Swiss government really cares about their citizens' opinion. For example, they not only ask them to vote on public referenda (Volksabstimmung). Through their VOX Analysis tool, the Federal Chancellery (Schweizerische Bundeskanzlei) seeks to gain an even deeper understanding of people's thinking after referendum results are in.

In 2014, the government declared an intention to modernise this tool which was originally conceived in 1977, almost 40 years ago. On August 17, the new plan was published: in future they will do their polling ... by telephone?

Telephone vs. Internet

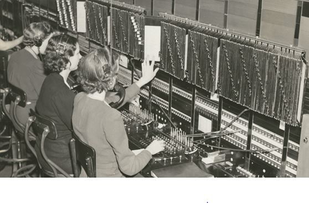

While Bell's 1876 invention still has its place, it is by today's standards neither a reliable nor an effective means to learn what citizens think. And often a rather annoying one for those called.

Telephone interviews suffer from the "social desirability bias" which is problematic when the goal is to inform political decisions. How many people answer completely honestly on their phone line about sensitive political issues, like their marihuana consumption or sexual preferences? Will respondents really tell what their true political opinion is when notions of patriotism or tolerance influence the interviewer's opinion of their character?

Telephone interviews suffer from the "social desirability bias" which is problematic when the goal is to inform political decisions. How many people answer completely honestly on their phone line about sensitive political issues, like their marihuana consumption or sexual preferences? Will respondents really tell what their true political opinion is when notions of patriotism or tolerance influence the interviewer's opinion of their character?

Asking 1500 random members of the general electorate will necessarily limit results to mostly superficial and simplistic findings, while the issues of the real world are getting more complex every day, as an unavoidable side-effect of human progress and increasing specialisation.

Asking Future Questions Is Non-Trivial

Worst, when asking people directly to predict the future, like the consequences of a policy subject to referendum, their answers will suffer from major cognitive mistakes.

At the 2014 ESOMAR Congress, I demonstrated some of those together with my fellow researcher, Jon Puleston. We asked the Congress participants to write down their own predictions to simple questions. How amazed were they - all clearly above average intelligent and knowledgeable - that their answers produced stark wrong results. For example, when simply asked to predict a coin toss, 68% of people will say "heads" which produces an erroneous forecast likelihood of 212.5% versus "tails".

This gives but a glimpse how the old ways can completely misguide a whole well-meaning and well-organised democracy.

A Proposed Solution

There are new, better methodologies to find out about the future than asking directly on the phone or in a questionnaire. For example on a prediction market, a coin toss (of a fair coin) forecast would not trade at 68% for longer than a flash. An alert trader would almost instantly sell the "heads" answer for 68% short and cover when prices normalise at 50%, for a quick profit of 18%.

We have evidence that Swiss people are quite good at participating in prediction markets which may be a result of their strong stock market culture. The Swiss National Television's SRF election prediction market produced significantly better forecasts than all traditional polls, irrespective of methodology, for both 2007 and 2011. The market forecast error was only 0.8%, whereas the big polling institutes GfS Berne and Isopublic had errors of 1.7% and 1.8% respectively. (Disclosure: Prediki's first generation software pro:kons was used by SRF.)

Switzerland should embrace the new methodology for more meaningful and reliable analysis of their referenda. The market prices would quantify the impact which citizens expect from proposed policies, the market talk would produce ample verbal material for further analysis.

This should be a permanent installation, allowing participation both before and after each referendum. The question should not be - or not only be - the rather hackneyed "How will the referendum turn out?" which is interesting for media but will not produce many deep insights into the real issues.

Rather, a well-designed battery of questions should ask the interested public to forecast the effects of the measures proposed by the policy, if adopted. These effects should be measurable by objective future national statistics relevant to the issue at hand. Not only should questions ask for the likelihood of the policy's desired effects, but also for undesired side effects which are often neglected or completely overlooked. A split in short-term and long-term effects - beyond the next election date - should counteract political myopia.

Everybody can participate

Every eligible citizen should be free to participate in this crowdsourcing tool or not. It is entirely natural that they engage more in areas which effect them directly or in which they are more knowledgeable. Without a better idea than the current forecast, it is not necessary that one trades in a particular question which makes the process very efficient.

Even after a referendum, the questions should be kept alive as trackers until the prediction horizon. This feedback mechanism will allow citizens to learn whether their assumptions and thinking were good, and continually help them to improve their use of the tool.

The Swiss Federal Council (Bundesrat) as the Federal Chancellery's parent agency will profit, too. More objective knowledge elicited from all citizens will help inform the implementation of new policies, help set priorities and provide an early warning regarding potential pitfalls, even once underway. The cost of capturing and aggregating citizens' opinion will be lower which allows either budget savings or the coverage of more topics.

Inviolable Democratic Principle

This new piece of democratic infrastructure will inform citizens, facilitate the inclusion of more specialised topics, a deeper debate, faster progress, and less error. There is a limit though, an important element which should stay the same and never be replaced: actual voting with one vote per citizen in the actual referendum.